until Abu Dhabi Autonomous Racing League

Extreme E’s transition to becoming Extreme H in 2025 is an undeniably impressive idea and gives the series vital chance to develop a new identity.

Aiming to raise awareness about climate change by racing in locations affected by it, Extreme E will add another string to its bow by adopting hydrogen power from 2025; a battery and a fuel cell will replace the electric powertrain currently used by the spec cars.

Promoting sustainability to breaking point

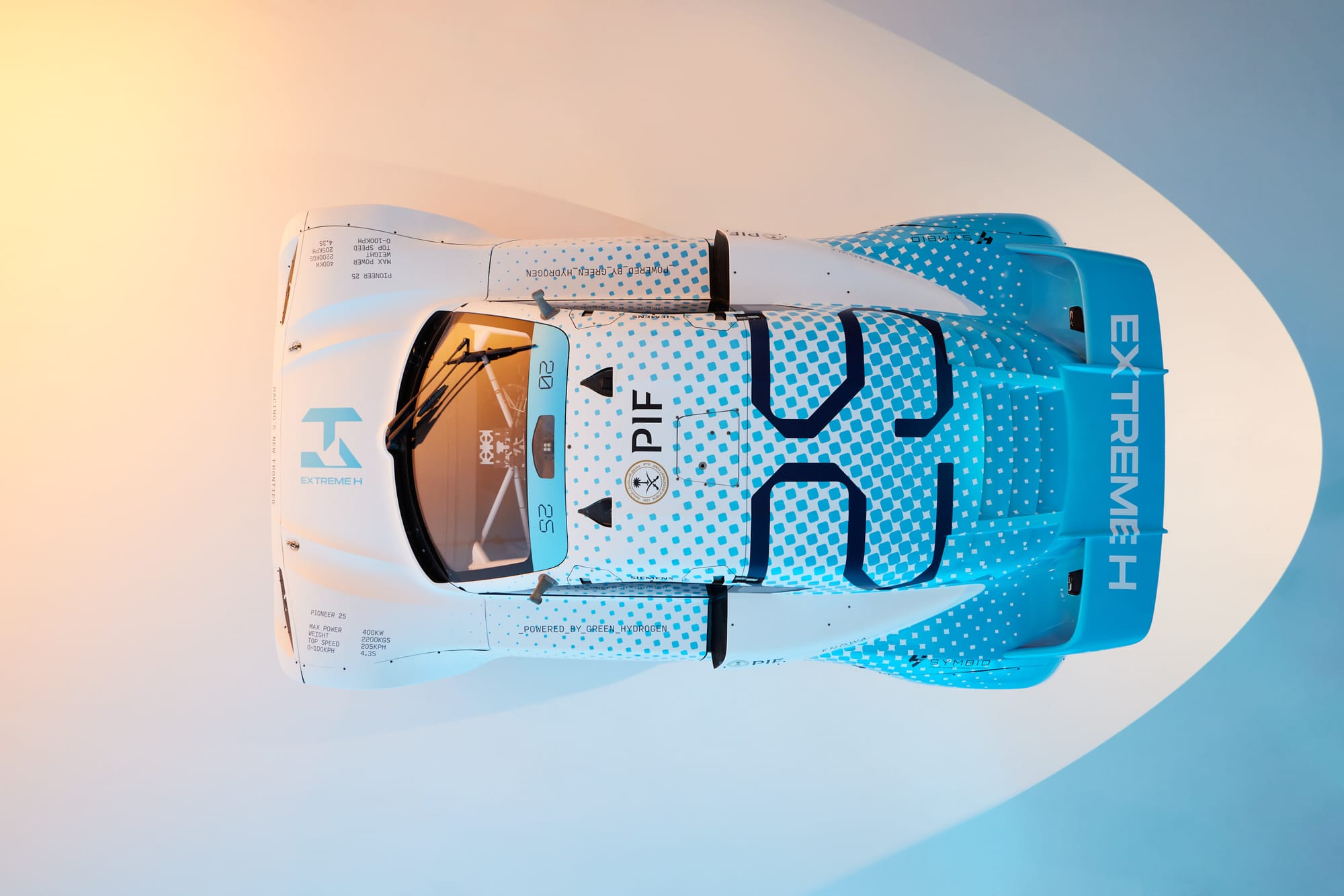

Last week, the series gave its new hydrogen car, Pioneer 25, its first public test with a run on the course in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland used for XE’s 2024 British round.

“Extreme H represents the first-ever testbed of hydrogen technology in motorsport, not just in our racing cars,but also in transportation, infrastructure, refuelling processes, and safety regulations.” said the series’ technical director Mark Grain.

“The Pioneer 25 has undergone an intensive testing programme to prepare for its debut, and this groundbreaking initiative positions us as pioneers in the field, showcasing the potential of hydrogen as a sustainable and powerful energy source.”

Hydrogen is a powerful energy source - combustible and more efficient than an internal combustion engine - and the work of Grain and his technical team to put it into a single-seater offroad racing car has been painstaking.

They had completed more than 1800 kilometres of testing ahead of the demonstration in Scotland, confirming the off-road abilities of the Pioneer 25 - which weighs 2200 kilogrammes but boasts a power output of 400kW (equivalent to 550 horsepower). According to the series, the car can reach 62mph in 4.5 seconds and scale gradients of 130%.

The series does however use the dreaded ‘sustainability’ adjective in press releases and advertising. Sustainability is a term that implies lots of things, such as technological development without negative consequences for the environment. It might mean something different for you; it’s a term that isn’t measurable.

As it becomes a hydrogen series and then the FIA’s first hydrogen-powered world championship in 2026, Extreme H must focus on shining a light on the pros and pitfalls of hydrogen production, sourcing, and adoption - if it truly believes that is the future of mobility.

Hydrogen: a grey (and green) area

As the world’s biggest industries slowly decarbonise, or investors seek ways to invest in different means of energy storage and production in case fossil fuel demand does drop, they might seek hydrogen as one of those answers.

Hydrogen is explosive and therefore effective as a fuel, and burning it releases no carbon dioxide (although it can emit nitrogen oxides). Compared with electric vehicles, hydrogen vehicles also do away with the bugbears of recharging, and ambient temperature doesn’t have such a significant impact on a hydrogen vehicle’s range.

There are also advantages when it comes to weight and energy density, which means hydrogen could well be a valid tool of lower-carbon mobility. Manufacturers such as BMW and Toyota are proponents of the technology, although there are many circles that believe hydrogen is best suited to freight vehicles.

However, money continues to be poured into electric vehicles and the development of solid-state electric batteries, which could prove transformative to electric mobility.

Incidentally, Extreme E’s transition to hydrogen led to Chip Ganassi Racing’s withdrawal from the series due to partner General Motors’ lack of interest in the power source.

Neither electricity nor hydrogen systems are without their flaws. For instance, battery production relies on intensive mining and can prove devastating: it has devastated some environments closely mirroring those in which Extreme E races.

In addition, storing and shipping hydrogen is difficult given it’s such a light element, and producing hydrogen is an expensive and energy-intensive process that can still produce carbon emissions and rely on using fossil fuels.

The main dilemmas concerning hydrogen at the present lie in its production. There are numerous ways to produce hydrogen, all of them denoted by colours: green, blue, grey, yellow, black or brown and turquoise.

“The hydrogen that we want to use and that we will use is green hydrogen, so produced with solar or wind [power sources],” said Extreme E CEO Alejandro Agag.

He continued: “I am also a big fan of nuclear power, so I wouldn't have any objection to using pink hydrogen for the championship.

“Definitely, the source of the hydrogen is key. It's key for the whole story and to make the picture credible, in order to make all the research, all the developments, all the advances that we want to do.

“Hydrogen is hydrogen. The molecule of green hydrogen is identical to the molecule of blue hydrogen [produced using natural gas], for example. But of course to be really credible to what we’re telling it has to be produced in a sustainable way.”

Green hydrogen is however one of the most expensive ways to produce hydrogen at the moment. Accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers estimates that it costs up to €8 per kilogramme to produce in this way, though that price could fall to €1 per kilogramme by 2050 - if infrastructure is built up and invested in at a projected rate.

Grey hydrogen meanwhile costs up to just €2/kg to produce - but it relies on coal or methane for its production and is therefore far worse in terms of greenhouse gas emissions.

That Extreme H has chosen the route of green hydrogen is commendable, but it seems that the series will continue to focus on tackling climate change apathy.

Extreme H’s golden chance

Before the Extreme H launch on its former Royal Mail ship - St Helena, which was docked next to the HMS Belfast - in June, Agag said his series had one overarching message.

“If you look back at five years ago, 10 years ago, the feeling of a climate emergency was a lot more in the front page of the news.

“Today maybe for some reasons… from wars that are going on to probably an amount of fatigue of listening to the same messages again and again, we have lost a bit of that sense of urgency, and that’s very dangerous.”.

Extreme E has attempted to spread that message, although it’s questionable whether the onus of climate change awareness should be put on fans of the series rather than the likes of massive investment firms and mining companies, some of whom operate in close proximity to some of Extreme E’s racing locations.

Those messages are diluted inherently by the fact that Extreme E races so far away from its fans, who tune into events remotely.

When Extreme H emerges from Formula E’s shadow to become the first hydrogen FIA world championship in 2026, it has the chance to shun its vague messages of sustainability and climate change awareness - and use hydrogen to power a genuinely substantial and interesting story.